Service Details:

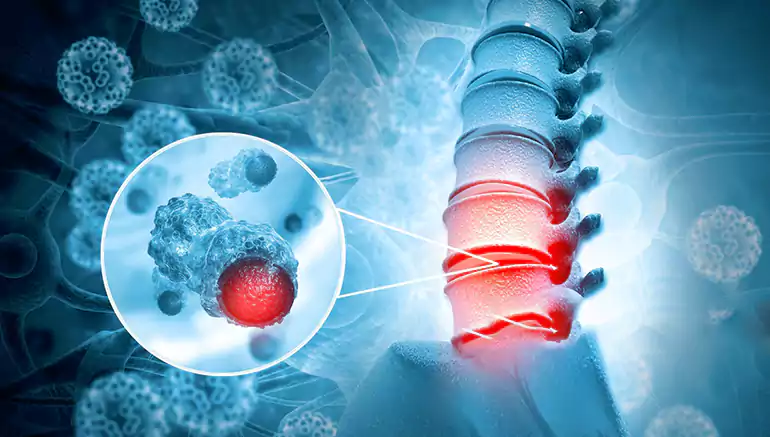

Spinal infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, leading to vertebral destruction, pain, and potential spinal deformity (Pott's disease). Data tracks inflammatory markers, imaging (characteristic vertebral changes), and response to anti-TB drugs.

Spinal tuberculosis, also known as Pott's disease or tuberculous spondylitis, is a destructive infection of the spine caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the same bacterium that causes pulmonary tuberculosis. It typically spreads to the spine hematogenously (through the bloodstream) from a primary TB infection in the lungs or other parts of the body. The infection usually starts in the vertebral body, often affecting the lower thoracic and upper lumbar spine, and can then spread to adjacent vertebrae, intervertebral discs, and surrounding soft tissues, potentially forming abscesses (cold abscesses) that may track along muscle planes.